It was a long, hot summer in Houston.

I remember because my family was busy working and sweating to build a restaurant. We were sweating both from the heat and the nervousness of opening a new family-owned business in South Park, an inner-city Houston community. The business was on Martin Luther King Boulevard nestled between Timmy Chan’s Fried Chicken and Rice and Harlan’s Barbeque. My parents were worried about being the fifth fast food joint along that part of the street. We had to price the fish and shrimp just right: low enough to attract customers, but not so low that we lost our profit margin. The competition would be particularly stiff on Friday nights after the football games and Saturdays with crowds from the beauty shops, local Kmart, and flea market. We created the $1.99 Fish Boat Special.

The boulevard, down from the University of Houston and south of the Shrine of the Black Madonna, had lots of day care centers, corner markets, and local schools, and it was littered with fast food restaurants. We had Burger King, Church’s Fried Chicken, and more chicken. I do not think we had a McDonald’s, but there was a homemade burger joint and portable boudin sausages wrapped in foil being sold all day every day on MLK. In the late ’80s the oil wells dried up. That was all that my mom said when she was laid off from Exxon. The booming real estate business my stepfather had also went bust. However, we were fortunate to be able to start a business. And what made sense for a family looking to grab hold of the American Dream? The fast food chain was the best way forward. We boldly mapped out the opening day and plotted to be a fast food seafood franchise that competed with the giants like Captain D’s and McDonald’s. Like superheroes, we declared to not only lift up our family from poverty but to provide jobs for the community and create wealth.

It was hard work that came with its share of strife: This worker quit and walked out; this person did not show up, and this person was stealing. However, for about ten years, the business sustained us and was transitional work for others.

As a family we worked in the restaurant countless hours. We employed neighborhood folks, the single moms, ex-felons, and young adults with limited skills. It was hard work that came with its share of strife: This worker quit and walked out; this person did not show up, and this person was stealing. However, for about ten years, the business sustained us and was transitional work for others. During a summer school class, a young Black male student showed me the crack rocks he was going to sell after class. He then asked, “What you gon’ do when you leave?” I responded, “I gotta go work at my folks’ restaurant … Fish Boat.” He said, “Oh, you the Fish Boat girl.” I got a hug and wink after class. He left through the side exit and disappeared, skipping the rest of history.

Today, MLK Boulevard looks desolate and forgotten. The gentrification engulfing the Third and Fourth Wards never made it to Martin Luther King. The neighborhood high school is fenced up and spray painted. What happened to wealth building on the boulevard? Why did the fast food restaurants and package stores lead to more poverty? Worse, today, with COVID-19, we see they have led us to an early death. The same people who dotted the streets over twenty years ago of any MLK street in any urban city are now suffering disproportionately from COVID infections and death.

Structural racism is the most influential form of racism at socioecological levels. Neighborhoods have limited access to fresh fruits and vegetables and high concentrations of fast food restaurants because of structural racism, and they are at-risk communities. It affects racial and ethnic health inequities and leads to health disparities.

Every proud Black fast food restaurant owner on that strip saw an opportunity to build a legacy based on the American Dream of ownership just like McDonald’s, Burger King, and Popeyes. Now, as the news cycle talks superficially about obesity as an increased risk factor for death from COVID-19, maybe it is not the fat cells on the people but the fat in foods they have been ingesting that is the real conversation to be had. Structural racism is the most influential form of racism at socioecological levels. Neighborhoods have limited access to fresh fruits and vegetables and high concentrations of fast food restaurants because of structural racism, and they are at-risk communities. It affects racial and ethnic health inequities and leads to health disparities.

As medical centers in Detroit, New Orleans, and D.C. grapple with the overwhelming death toll of Black Americans from COVID-19, they are identifying burdens of other comorbidities, such as obesity, heart disease, and asthma. However, we need to also study the zip codes of these deaths just like we do in homicide cases. Social segregation, a clear example of structural racism, is the co-conspirator with COVID-19 and must be recognized as well.

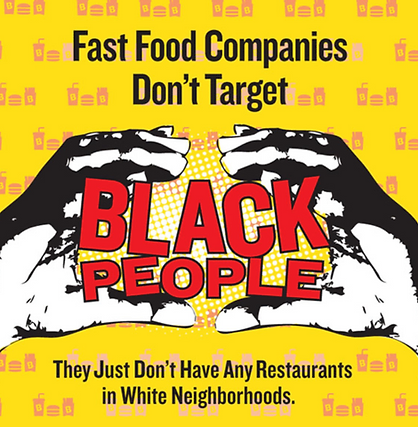

My great aunt lives in West Philadelphia, which is a food desert, and my aunt in Harlem lives in a food desert too, despite gentrification. The history behind the rise of fast foods in Black communities comes out of a need, not an intent. Because of social segregation and the sheer mass of Black people in one area, Black communities present an overwhelming working demographic that is fertile land for the fast food industry whether it be local or corporate owners.

Even today, some of these communities will never see a Starbucks or a Dunkin Donuts. Residents in Black communities that lack wi-fi have to go to McDonald’s. The economic and community importance of the Golden Arches are illuminated over the rising known health risks that are associated with fast food.

In the early 2000s, the medical community was sounding the alarm on the growing problems of obesity in Americans overall. A product of Chicago’s South Side, Mrs. Obama in 2008 created her White House Initiative, the Let’s Move campaign coupled with a garden, in response. Dr. Naa Oyo Kwate of Rutgers University Department of Human Ecology and Africana Studies wrote a revealing paper over ten years ago called “Fried Chicken and Fresh Apples” in which she explores the reasons Black communities are heavily dense with fast food.

The professor explains that racial residential segregation has created four major pathways that have allowed fast food restaurants to proliferate in Black communities. The main one was the economic conditions. Kwate states, “Segregation fosters a weak retail climate and surplus of low wage labor, both of which make the proliferation of fast food profitable.” She points out clearly that even if a “Black neighborhood” is of a similar property and price as a white neighborhood, Black homeowners suffer a “racial tax” and are still stigmatized, leading to an environment where only fast food businesses will bother to build and invest in the community.

Professor Marcia Chatelain, a native Chicagoan and historian at Georgetown University, asked herself the same question I did. What was the history of these fast food establishments in my community? In her interview on NPR about her book Golden Arches, she added to Professor Kwate’s themes and emphasized the marketing strategy that McDonald’s and others use to become valued in the community. McDonald’s became a source of youth employment and scholarships. It became a social place to meet for coffee. Even today, some of these communities will never see a Starbucks or a Dunkin Donuts. Residents in Black communities that lack wi-fi have to go to McDonald’s. The economic and community importance of the Golden Arches are illuminated over the rising known health risks that are associated with fast food. Do you want fries with that shake, or supersize me, or McDonald’s college tuition scholarship offers at some point became less than a bargain for Black communities.

On December 21, 1968, Herman Petty marched into history and became the first Black man to own a McDonald’s franchise. This ex-military man was strategic in setting up his business at 67th and Stony Island. He was the leading Black businessman in Chicago, a real champion for his people. His name would be synonymous with the Golden Arches and success. He and my parents and many others had noble dreams of economic empowerment while living in the midst of structural racism. A satellite view of Martin Luther King Boulevard today shows the empty lot where Fish Boat was, and down the street still stands the liquor store and the original Timmy Chan’s Fried Chicken and Rice. This area has no political or economic value, and the labor for the fast food restaurants is still abundant, except there are not many businesses anymore. Instead of a public health message about how obesity leads to earlier deaths due to COVID-19, perhaps we need to address the social segregation of neighborhoods that have allowed food deserts to persist in Black communities for decades.

Also read the interview with Dr Naa Oyo A. Kwate and listen to the podcast on this subject by clicking on the button below: